Dr. Richard Kortum of ETSU traveled to a remote area of the far-western Altai Mountains near the borders of China, Russia, and Kazakhstan. "You realize this is the closest thing to being on another planet," he said.

JOHNSON CITY, TN - In the summer of 2002, during his second visit to Mongolia, Dr. Richard Kortum, an associate professor in the East Tennessee State University Department of Philosophy and Humanities, traveled to a remote area of the far-western Altai Mountains near the borders of China, Russia, and Kazakhstan. Kortum was in search of petroglyphs-carved pictures on rock faces created by prehistoric artists. His Kazakh guide remembered seeing such things decades ago in a remote valley characterized by rock-filled mountainous terrain, an unforgiving climate, and a sparse population of nomadic herders.

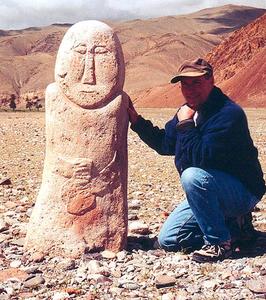

After a bone-rattling journey in the pre-dawn through the trackless mountains, the two men climbed out of their Russian jeep at a cluster of three high, snow-capped hills. They encountered fantastic images of animals, humans, wheeled vehicles, and strange anthropomorphic figures on a glacier-smoothed granite boulder the size of a house. Kortum scoured the topography and discovered increasing numbers of lively images, along with 3,000-year-old Bronze Age burial mounds, stone circles and squares, enormous standing stones, and carved stone men from the Turkic era, some 1,400 years ago. Since that day, Kortum has made

this rich site a focus of his cultural and art-historical studies.

Kortum's wife, Theresa Markiw, an American diplomat, was assigned to the embassy in Mongolia's capital, Ulaanbaatar, for two years. Even though she has now been posted elsewhere, Kortum leads an expedition every summer to Bayan Olgii province, and to the high Altai, where he sets up camp beneath the three hills-Biluut 1, 2, and 3-at an elevation of nearly 8,000 feet.

Initial support for his work came from major grants awarded by the ETSU Office of Research and Sponsored Programs in 2003 and 2005.

"When you pull up to an encampment of 'gers' (the word rhymes with "pairs," and they are the round, felt-covered tents also known as "yurts") and observe a diminutive, copper-skinned woman milking a horse," Kortum says, "you realize this is the closest thing to being on another planet."

The region has only recently been opened to outsiders after seven decades of Soviet control. Russian maps from 1942 indicate the presence of ancient burial sites in the vicinity, but, until Kortum arrived, no one had documented these petroglyphs. The head man of a family of nomadic herders told Kortum that he was the first outsider they had ever seen. Before the rest of the world creeps into the area, bringing looters and graffiti, Kortum is striving to record the archeological treasures.

Kortum has already published two papers on his discoveries in a leading international journal and a third is forthcoming next year. Two conference presentations are scheduled and four collaborative papers are being prepared. A major book project is planned, and an interactive 3-D mapping and online database for international scholars will result.

This past summer, Kortum was awarded an ETSU College of Arts and Sciences Faculty Summer Research Fellowship. He returned to Biluut with ETSU geologist Dr. Mick Whitelaw, honors student Taylor Branham, former ETSU surveying faculty member Dr. Jerry Nave, and a noted Mongolian archeologist, Dr. Yadmaa Tserendagva, to map as many petroglyphs and surface monuments as possible during their four-week venture. The team selected the middle hill, Biluut 2-the one with the least number of images, for the first phase of their mapping project.

Despite fierce winds, drenching rain, snow squalls, and unreliable power sources, the team pinpointed some 1,600 petroglyphs, even as they contended with inquisitive travelers and grazing goats, horses, camels,

and yaks.

Kortum estimates the number of glyphs on the other two hills may be as many as 7,500-8,000. "There are hunt scenes, combat scenes, magical or mythological figures, and ceremonial or sacred imagery that is difficult to interpret, but probably involves Shamanism-a form of religious practice still very much alive in the region."

In addition, Kortum and his colleagues identified some 100 Bronze and Iron Age mounds, circles, squares, stelae, and Turkic structures situated near Biluut 2. "We have really just begun to scratch the surface of this incredibly rich complex," he says.

Kortum is engaging the services of two experienced archeologists, Dr. Jay Franklin in the ETSU Department of Sociology and Anthropology and Dr. Francis Allard of Indiana University of Pennsylvania, who has

extensive experience excavating Bronze Age mounds and rings in western China and central Mongolia.

In future expeditions, this team will explore the enormous variety of prehistoric man-made features around Biluut 1, 2, and 3. Near the study area are located giant spiked circles of rocks, many the size of a football field.

This area of Central Asia was a major crossroads throughout a vast epoch of prehistory and witnessed great transitions in cultural economy and the development of early technologies. From the upper Paleolithic through the Bronze, Iron, Turkic, and Mongol periods, migrations of European, Siberian, and East Asian cultures came into close contact, but much of the area's past is shrouded in mystery.

Kortum hopes to unravel some of the many important questions surrounding Mongolia's history. He enjoys collaborating with international experts in the field, including the University of Oregon's Dr. Ester Jacobson-Tepfer, the leading scholar on Central Asian rock art; Dr. A. Ochir, Director of the National Museum of Mongolian History; and D.

Tseveendorj, Director of the Institute of Archeology of Mongolia's National Academy of Sciences, the leading Mongolian expert on Altai petroglyphs.

"Mongolia feels like home to me," says Kortum. "Although I don't believe in such things, the first time I journeyed across her vast steppe and set eyes on a ger, the moment I drank my first bowl of airag (fermented horse milk), I felt I belonged there-that I had lived there long ago. I can't explain it. All I know is that I can't wait to return."

For further information, contact Kortum at (423) 439-6492 or via kortumr@etsu.edu. His Web address is http://faculty.etsu.edu/kortumr/bio.htm.