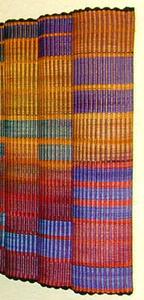

A close-up detail of a John Gunther wall sculpture.

The world of textiles and fiber arts is as varied as the people who find creative arts interesting. This month A! Magazine features tapestry artists and weavers who create "fiber paintings."

John Gunther (Click here to see John's photo gallery.)

Since 1973 John Gunther of Abingdon has created contemporary rugs and sculptural wall hangings. With work in both two- and three-dimensional forms, he creates abstract, graphic, and representational pieces, both functional and non-functional.

Self-taught, Gunther works primarily in wool. He has explored the textural qualities of the Scandinavian warp-faced technique of the Ripsmatta weave, combined with the hand-dyed relationships of color. Weaving on a floor loom, Gunther produces depths of field not usually found in fiber media. The artistry of his hand-painted yarns provides an endless palette of color and tone.

Most recently his art has taken a new direction. Previously he used bright, rich colors. Now his repertoire includes wood-framed "fiber paintings" - subtle, more watercolor-like weavings for a soft, ethereal effect.

Gunther explains, "My contemporary artwork consists of a kind of fiber painting technique that remains unique in that I dye my fiber first, then weave it on a floor loom. Since they are hand-dyed, natural color shifts occur by the dyes when changing from one color to another. The fundamental nature of a finished piece provides prominent colors with complementary accents."

His weavings represent his interest in natural phenomena and landscapes, geographical locations, and space. "I love working with color and enjoy the creative freedom [that weaving] allows me within the confines of a complex textile," Gunther states.

Gunther begins his weavings with two warps of natural white Merino wool yarn which is custom spun in New Zealand. This wool is known for its ability to take on dye with brilliance. Variations in the weaving process can create pieces suitable for wall tapestries as well as durable floor coverings. Wall pieces vary from single pieces to diptych (double) and triptychs (triple pieces) with multiple layering of pieces to create a three-dimensional sculptural effect. He typically constructs his mountings and makes his own hardwood frames.

Gunther's studio is located on the outskirts of Abingdon on a six-acre hillside with commanding views of the two highest peaks in Virginia: Whitetop and Mount Rogers. He participates in at least 20 fine art and art/craft shows a year. His work has been exhibited and represented nationwide and abroad in galleries, shops, and art shows, as well as in private and public collections.

Ellen Patrick (Click here to see Ellen's photo gallery.)

Growing up in the Mountain Empire region, Patrick says she was always surrounded by fiber art. "My grandmother and aunt would make quilts and sew clothing from scraps. It was always very peaceful to watch and do," she recalls. "I had close friends who were weavers when I began graduate school and was drawn to this medium."

Today, Patrick says, "Inspiration is all around me, especially the mountains with their strength. I can express this in a simple triangle. Artists who greatly inspire me are Georgia O'Keeffe with minimalism and Kandinsky with spiritualism."

Patrick's weavings are framed and more of an abstract nature. Some are in two pieces, others in three. She says, "I chose to frame my tapestries to give them boundary. The frame for some adds to the design. Framing weavings, in itself, is not significant, just that a tapestry is similar to a woven painting. As in any medium, the artist may combine elements to achieve an end."

The largest pieces are five feet in height and three feet wide. The smallest is only four inches high and three inches wide. The weavings pictured here are all made from 100% wool, but Patrick also uses paper, sticks, and beads. She utilizes two types of looms, a jack-style four-harness loom and a table tapestry loom.

Patrick earned a master's in fine art (in framed tapestry) at East Tennessee State University. Her undergraduate work was at Virginia Intermont College in her hometown of Bristol. She currently lives in Abingdon and has been teaching art in the Bristol Tennessee City School System for 29 years.

She says, "As an artist, I bring to my teaching a connection - by doing what you love, you are better able to share that information with others."

Carol LeBaron (Click here to see Carol's photo gallery.)

LeBaron began creating textile art in the 1970s when she lived on a farm and raised sheep in Tillson, New York. She wove mandalas and handbags from handspun wool and sold them at craft fairs before entering the Rhode Island School of Design where she did undergraduate work in weaving.

Today, LeBaron's work is a combination of contemporary aesthetic, modern technology, and ancient techniques. Materials include wool and cashmere for the clamp resisted pieces, while her Jacquard work combines merino wool, rayon, and other synthetic fibers.

LeBaron's clamped wool and Jacquard works have been exhibited nationally and have won several awards. Her work has been published in the Surface Design Journal. In 2005, her works were featured in the Tennessee Arts Commission Gallery in Nashville.

She has received a major research grant for her "resist" explorations on wool. For the past five years, LeBaron has been experimenting with various "resist" techniques on wool. She explains, "Clamp resist is one of the oldest forms of pattern application to textiles. Ancient techniques are juxtaposed with computer software and a Jacquard loom to recreate clamped wool pieces using a combination of merino wool and synthetic yarns. In some cases I screen print or fold the fabric to create the illusion of repeat. Often I piece small sections together in order to create patterns. All of the stitching is done by hand, in order to both conceal the [stitching] and cause it to be present."

She continues, "The work I have done with felt and clamp resist techniques is a new process that I have developed from ancient practices of resist dye. Many laymen may have heard of the term 'shibori' (the Japanese word for simplified tie-dye). In traditional techniques done in China and Japan, textile designers use square boards and dip the edges of their fabrics to make geometric patterns. They typically use cotton or silk. I explored new avenues in this technique, using acid dyes that are meant for wool, and exploring the way in which different kinds of wood and varying pressures would change the imagery."

LeBaron uses the textile medium to express weighty concerns, especially the devastating effect of human impact on natural forms and environments. She says, "Colors and forms in nature and the landscape inspire me. This can be either the beauty of a natural landscape or the color and texture in industrial cityscapes. On a conceptual level, it becomes the impact of man on nature. The forms I find in nature express these concerns. I express human impact on natural forms and the internal landscape of the psyche using colors taken from photographs of devastation caused by acid rain, warfare, and other environmental pressures. My raw material is a combination of memory and observation. Plant forms and cell structures are expressions of emotion."

While doing a senior residency at Oregon College of Arts and Crafts, LeBaron visited an old growth forest for the first time. "The experience had a profound effect on me," she says. "As a result I have begun to explore color as a way to express human impact on natural land forms. The work contains color taken from satellite photographs and images of colors created by acid rain, warfare, and other environmental pressures."

She adds, "As my process with new media develops, I find that my dependence on the dye pot and the computer are equal. I abstract shapes onto wood and transform them into pattern through clamp resist, screen print, and piecing. Clamp resist allows the image to penetrate the fabric, creating an opposite on the other side with an edge unobtainable with any other method. I alter this line by changing shapes, varying pressure, and using different kinds of wood. This unique 'fingerprint' is then digitized."

Abstraction and repetition are LeBaron's visual language. Her facilitator is a computerized Jacquard loom. With a Jacquard loom, the artist may select individual threads rather than groups of threads, allowing an intricacy of design not possible with other looms.

She says, "Jacquards are woven on an industrial loom, creating a literal and conceptual opposite to ancient, hand-controlled processes. I scan the pieces into a computer and manipulate them into repeat pattern. Whether the code is embedded into the structure of the material through jacquard weaving, or imprinted onto the surface by means of inkjet printing, the output device is a translator. Countless complex patterns move 'inside' the material in a fluid process between the finished jacquard pieces and the dye pot."

LeBaron teaches crafts and Western tradition at Emory and Henry College, sculpture at Virginia Highlands Community College, art history at ETSU, and in the fibers department at Georgia State University in Atlanta. She has taught at the Appalachian Center for Crafts and at the Rhode Island School of Design where she received her MFA. She received her BA from Smith College, in Northampton, Mass., in photography/printmaking and art history.