George Huber

We asked George Huber, a retired Tennessee Eastman executive who lives in Bristol and is active in several musical organizations to reflect on the importance of opera in his life.

A Magazine: What was your introduction to opera?

George Huber: I was fortunate to grow up in the 1950s and 1960s in the public high school system in Dallas, Texas, where I had many excellent teachers and cultural opportunities. When I was in sixth grade, my music class went to the State Fair Music Hall to see a student performance of “La Bohème.” It may have been only the first act, but I will never forget the soprano’s “Mi chiamano Mimí” and those soaring high C’s of Rodolfo and Mimí on “Amor, amor” at the close of the act. That made an enormous impression on me. I had never conceived that such beauty in music and drama could exist.

I certainly never dreamed that years later I would be singing in operatic productions on that same stage.

A Magazine: And how did that come about?

Huber: Even as a small child, I loved music but never imagined I could sing. I grew up on the music of the 1950s and ’60s: Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Everly Brothers, Peggy Lee, Sam the Sham, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry. But I could remember all those songs, and I still do to this day. It’s like I have a tape recorder in my head — a really handy tool for a singer.

My three sisters, all a bit older, had a trio in church: soprano, alto, tenor. They were pretty good. But since my voice hadn’t changed yet, I was still a soprano. I used to try to join in and they would yell “Shut up! Shut up!” so I would go out in the backyard and sing to the dog. I guess that’s how I became a soloist.

A Magazine: Did you study music after that?

Huber: I didn’t intend to. I was deeply into mathematics, but I started singing character parts in my high school musicals — I played the Stubby Kaye character Nicely-Nicely Johnson in “Guys and Dolls” and got to sing the great “Fugue for Tinhorns” that starts off the first act and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat,” a big solo for a high school kid.

Once I graduated from high school, I was accepted into Yale University with some generous scholarship help. Even though I started out majoring in math, I soon switched to music. I simply couldn’t help myself and wanted to be a professional opera singer.

A Magazine: What was studying music at Yale like?

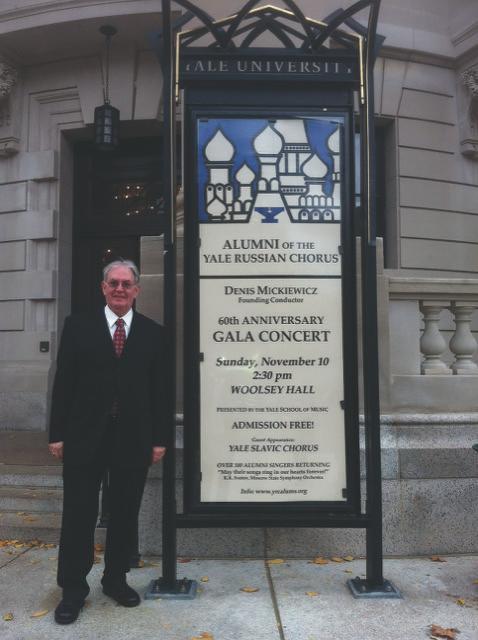

Huber: It was an amazing exposure. I tried the Yale Glee Club, but it was too Joe College for my taste. Then I heard the amazing Yale Russian Chorus and auditioned as a freshman — the only year of my life I was a true first tenor. I still sing with the combined alumni and undergraduate Yale Russian Chorus contingents on occasion. Three years ago, I conducted a small alumni group in some concerts at a choral festival in Italy. Unfortunately, they still insist that I sing first tenor, even though I’m a baritone. It’s a big difference. But I love Russian music to this day. There is so much wonderful Russian music, even orchestral works, that is neglected in the West.

A Magazine: Did you hear many professional musicians at Yale?

Huber: Too many to count. Yale had top-notch free concerts for the university community at Woolsey Hall and other venues around campus. I developed an early love for Wagner. Probably the foremost musical treat of my life was getting to hear the dramatic soprano Birgit Nilsson live in concert. She was, and still is to many, the foremost Wagnerian soprano of the second half of the 20th century. Okay, maybe ever. This would have been in her prime, 1969, I think. It was the most stunning and largest voice I have ever heard in my life, but completely unforced and also capable of very soft pianissimos. She sang “Dich, teure Halle” from “Tannhäuser” and the Liebestod from “Tristan und Isolde,” of course. The most memorable aria to me, though, was “Ozean! Du Ungeheuer” from Weber’s “Oberon.” It’s a slow, scenic aria painting the sea with waves and seabirds as Rezia waits on the shore for her lover to return in a ship. Then a faster cavatina ensues as she spies his sail in the distance, and the soprano’s voice rises to a climactic high C. Even though I was many yards from the stage, I was absolutely deafened. But her artistry was every bit as magnificent as was her natural instrument.

A Magazine: Who else did you hear or perform with at Yale?

Huber: Dozens of great artists. Beverly Sills singing all those Bellini and Rossini arias at Yale shortly after she made that famous LP with all the excess ornamentation — and before the Three Queens shortened her vocal career. Leontyne Price performing “Pace, pace mio Dio” and “Sur mes genoux, fils du soleil.” Leopold Stokowski conducting his wonderful orchestral transcriptions of the Bach Toccata in D Minor and Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” with the Yale Symphony Orchestra. Father and son violinists David and Igor Oistrakh in concert. Joan Sutherland singing Juliette, Gilda, and “Lucia di Lammermoor.” Everyone loved her, she could do no wrong. I got to sing in the chorus of the Verdi “Requiem” with four soloists from the Metropolitan Opera, including soprano Martina Arroyo and mezzo Maureen Forrester.

A Magazine: What was your formal education at Yale like?

Huber: I wish I had been more mature and diligent, and applied myself more. Both of my voice teachers were tenors, so they tried to train me as a tenor. It was after I graduated that I started singing baritone, where my voice naturally lies. I studied intensive Russian for a year, French for two, and I learned Spanish for four years in high school. And like music, I am fortunate to be able to remember much of that. I received a wonderful, well-rounded education in counterpoint, medieval and Renaissance music, Romantic music, art history, social sciences, pure math and history of music. I conducted the Yale Russian Chorus in a few rehearsals when the regular conductor was late or unavailable. But many of my most profound experiences were out of the classroom. The Yale Art Museum is totally world-class, as are its collection of historical musical instruments and its amazing libraries.

After my freshman year, in 1968, I went on a summerlong concert tour of Eastern and Western Europe with the Yale Russian Chorus, a mind-boggling experience that bolstered my lifelong love of travel and foreign languages.

A Magazine: After you graduated, how did you further your professional career as a singer? Did you ever sing in “La Bohème?”

Huber: Well, most importantly, I moved back to Dallas and found a competent teacher, Madeline Sanders. As soon as I opened my mouth, she said, “You’re not a tenor.” I trained with her for the better part of a decade. It grounded me in a vocal technique that has endured pretty well for many years now. But I knew all the tenor arias and roles, not the baritone ones. I had to learn all of those.

I did the things that aspiring opera singers do. I sang Broadway songs, Russian and Italian songs, arias and ensembles in an Italian restaurant with other aspiring singers. I did dinner theater and sang commercial jingles in a professional recording studio. I sang weddings and funerals. I did an occasional “big gig” such as the Brahms Requiem, Vaughan Williams’ “Five Mystical Songs” or the Fauré Requiem. Lots of Messiahs. I was a paid section leader over a period of more than 15 years for just about every Christian denomination. I was a member of the Lake George Opera Workshop in summer 1979, singing with the wonderful tenor Jerry Hadley in “The Barber of Seville.”

It was in Lake George that I got to sing a lot of the music from “La Bohème” myself, furthering my appreciation for Puccini’s marvelous, natural compositional techniques. Even though “Bohème” and other Puccini operas are considered part of the verismo movement, “Bohème” stands out as being about real people. There are no ice princesses like in “Turandot,” or Western cowboys caricatures as in “La Fanciulla del West;” these are people of “carne e d’ossa,” “flesh and blood” as the baritone sings in the “Prologue” to Leoncavallo’s “I Pagliacci,” another famous (and ferocious) verismo Italian opera.

In “Bohème,” two couples are truly the protagonists, amid a gaggle of subsidiary characters. The seamstress Mimí and the poet Rodolfo—soprano and tenor, of course—fall in love, gloriously, in Act I when they meet in a Parisian garret. (But even then, her health is delicate.) The painter Marcello, baritone, is in love with the beautiful and flirtatious Musetta, of “Quando m’en vo” fame. Puccini’s compositional genius makes the standard “aria for him/aria for her/duet for them” structure of so many operas sound the most natural and beautiful musical structure, eliminating any other possibility to achieve the essence of the art and drama. This is even evident in Act III of “Bohème,” where you can hear a quartet that is really two different duets occurring simultaneously. Marcello and Musetta are quarreling again and calling each other names, while Rodolfo and Mimì have agreed, despite their differences, to stay together until the spring (“alla stagion dei fior”). It’s a convincing unity of diverse elements.

In my own career, I started getting some breaks at around age 30, when I had a secure technique as a baritone and some roles I could sing (but had not). I was in the Dallas Opera Chorus in 1979–80 and 1980–81 and had a small “featured” role in “The Ballad of Baby Doe.” They were still at the Texas State Fairgrounds in that barn of a theater; this was years before Dallas built the wonderful Winspear Opera House downtown.

But I learned more about solo and choral singing, acting, and new roles in those two years at Dallas Opera, and sang with more wonderful singers. The conductor was Maestro Nicola Rescigno, who gave the legendary soprano Maria Callas her start in America in 1957, the Dallas Opera’s debut year. The chorus master was the ageless Roberto Benaglio, who was also chorus master in Vienna and at La Scala in Milan. He coaxed incredible (and credible) sound out of the Dallas chorus using only 15 words of English.

I was privileged to hear the great soprano Renato Scotto in Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” and as Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut.” I didn’t mind being a spear-carrying chorister in “Aïda,” since I got to hear the dramatic tenor James McCracken as Radamès, in a love triangle with Marilyn Horne as Amneris and the underrated Mexican spinto soprano Gilda Cruz-Romo in the title role. Those ladies sang such a fierce confrontation scene, they nearly chewed each other’s faces off. Everyone loved Ruth Welting as Baby Doe, the page Oscar in “Ballo” and as Lakme, another sweet, lovely soprano with incredible high notes. Frederica von Stade, or “Flicka” as she is universally known to friends, was the most generous, giving singing actress I ever performed with, as Cinderella or La Cenerentola in the Rossini opera. “Cenerentola” is truly a seven-person ensemble opera, requiring virtuoso singing and acting on the part of all the singers. She had a melting smile, great, noble beauty, stunning technique and an amazing stage presence. And Paolo Montarsolo as the gaunt, goofy, pompous Don Magnifico gave a master class in basso buffo acting and singing.

Dallas Opera and my many years singing with the Yale Russian Chorus have left musical impressions that I hope will endure as long as I do. I hear many of those great voices still today in my mind, their nuances, how and when they breathed. It was a great blessing.

A Magazine: Do you still sing professionally today?

Huber: I consider myself as a “professional-quality” singer now. As I began to seriously audition for opera companies in my early days, I came to some hard realizations. It is a lonely job that requires tremendous discipline, stamina, single mindedness—and a big bankroll and world-class voice don’t hurt, either, until you become completely established. I had none of those things. I missed leading a “normal” life, settling down, getting married. Singing was no longer a joyous act, a devotion, a passion. It had become a job. I sang in the San Francisco Opera auditions one year and came in second. If I had come in first, I would have had a major role: perhaps “Barbiere di Siviglia,” maybe “Rigoletto.” But second got you zip, nada. Then I auditioned for the Met Regional Auditions. I was age 34, my father had passed away a couple of weeks earlier, and I sang poorly. I decided it was time to Do Something Different. I didn’t know what that was, but it worked out just fine. I still sing in my choir at First Presbyterian Church in Bristol Tennessee, but now I freely give back to God the gift he gave to me originally. I still practice daily and learn new music. I sing solos when I can. I sing with the Yale Russian Chorus Alumni. I try not to crack my high notes, but if I do, life goes on. It’s fun again.

And it’s amazing how things work out. I worked for Eastman Chemical Company for years as a communications manager, doing lots of international travel and trade shows, including for their Latin America region. All those language abilities came in handy. I actually learned Italian three years ago to go to Italy and conduct our Russian Chorus concerts there. Some of the Eastman employees would golf wherever they went; I would go to the opera. I’ve been to the Met a dozen times or more, to La Scala in Milan, Covent Garden in London, the Staatsoper in Munich, the Teatro de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, Teatro Colòn in Buenos Aires. I heard Deborah Voigt sing the Empress in Strauss’s “Die Frau Ohne Schatten.” And back in Dallas, finally at the Winspear Opera House, I got to hear the world premiere of Jake Heggie’s “Moby-Dick” with tenors Ben Heppner and Stephen Costello in 2010. I have no regrets, and the best of both worlds: A lifelong passion for music, and a fun hobby. I wouldn’t change a single thing I’ve done. Who can?

To hear Huber conduct (and sing first tenor) in a performance in Old Church Slavonic of Nikolai Kedrov’s “Our Father,” go to YouTube and search for “Yale Russian Chorus Alumni Otche Nash.” There are many other performances on YouTube of the Yale Russian Chorus Alumni in small and large ensembles.