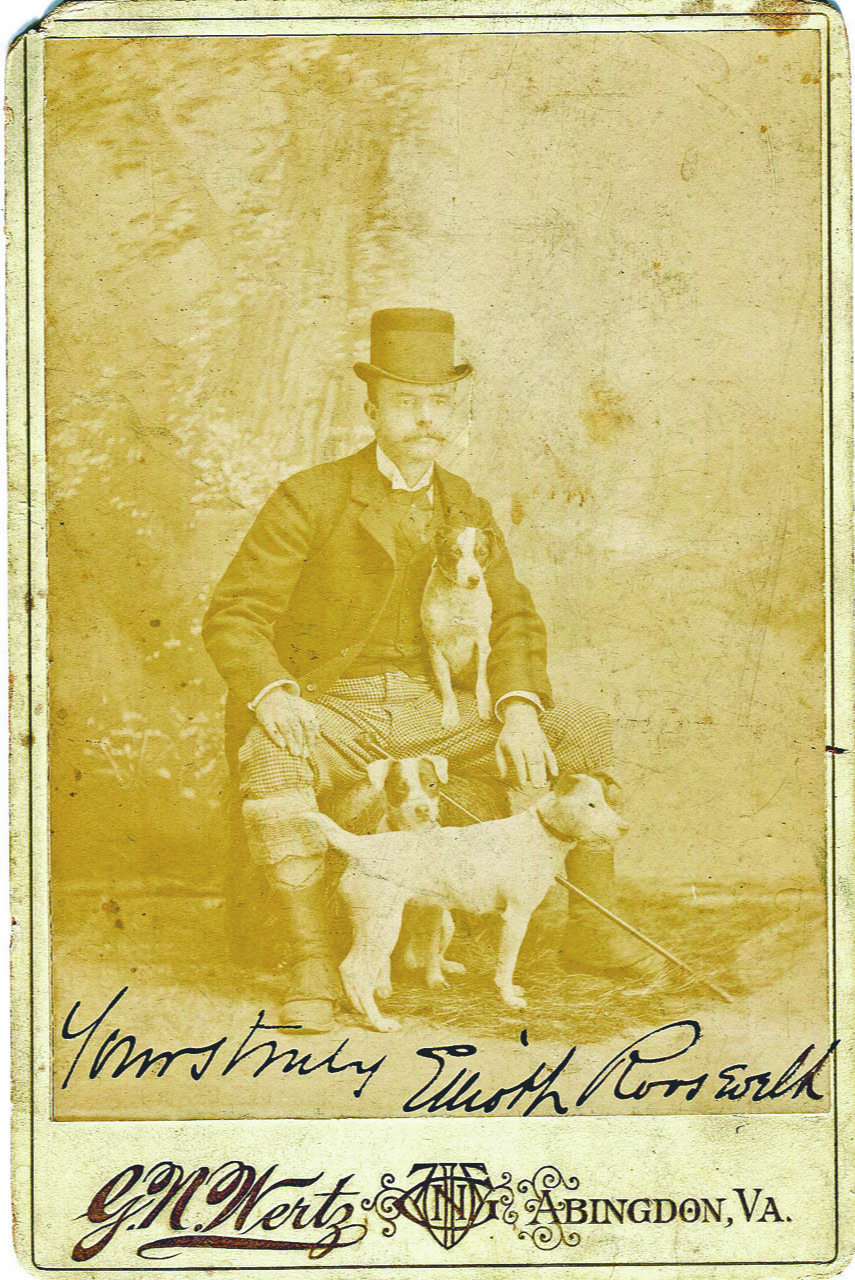

Photo by George Wertz of Elliott Roosevelt (Courtesy of the Historical Society of Washington County, Virginia)

You live life looking forward, you understand life looking backward. – Søren Kierkegaard

The newest exhibit at William King Museum of Art, Abingdon, Virginia, “Looking Back,” is a meaningful illustration of the connection between the present and the past. The exhibit features the beginning of photography connected with current technology. The digital exhibit features primarily the photography of T. R. Phelps and George Wertz.

“The exhibit started out as a looking back at our area – Washington County and Abingdon in particular – through photography. We knew the Historical Society of Washington County had been doing a project for the last 10 or so years inviting people to bring in their old photographs. They scan them and then put them in their media center. We felt that would be a nice partnership. This exhibit is a wonderful record of time gone by primarily from two photographers Phelps and George Wertz, and some of those community submitted photographs” Betsy White, museum director, says.

The museum had used a few Phelps photos in a previous exhibit. The exhibit featured miniature models of historic houses that were created by a Big Stone Gap artist through the WPA program. Phelps’s photos showed the houses in their historical context.

“The digital aspect came about because of Drew (James Andrew Walton). He’s at the end of a two-year fellowship with the Decorative Arts Trust. It occurred to me this would be a great way to showcase his fellowship and share it with the community in a meaningful way. The exhibit will be digital. The Historical Society doesn’t have the original photographs, and it would be laborious to develop in a darkroom. Plus, we were worried about too much light on any original images. So, we thought we could do a digital exhibit. It will show off our new digital lab and highlight Drew’s efforts. He has been scanning the glass negatives,” White says.

“Ninety percent of the exhibit is digital. We’ll be projecting images onto screens or on panels. We do have a few artifacts we’re showing in service to the main show, such as T. R. Phelps’ camera and case, and a few other things,” Walton says. There will be a guide keyed to each image and a place for the public to identify people they recognize. The images include town and country images, portraits, daily life and landscapes.

Both photographers took portraits to earn money to support their families. Wertz’s most famous photo is “Birdseye,” a panoramic view of Abingdon. The photograph was inducted into the Library of Congress and has been preserved by them. Wertz worked from a studio train car, called a Skylight car. He also took a photograph of Elliot Roosevelt when he was in the area being treated for his alcoholism.

Phelps traveled the area doing portraits and as a salesman, but he couldn’t resist landscape photography and photos of people’s lives. At the beginning of his career, Phelps carried his equipment on horseback.

“Most collections of photographs of life in Appalachia during this particular time period portray the industrialization of the region and the quality of life in the coalfields. Often these collections present an image of Appalachian people as hapless victims of exploitation. The Phelps photographs are remarkable in their own right, but they are especially important because they present an entirely different perspective of life in Appalachia during the early part of that century. They vividly illustrate the nature and diversity of social, economic and cultural activities in a non-coal area and offer pictures of independent people in charge of their own lives and futures,” Dr. Stephen Fisher, of Emory & Henry College, wrote in the early 1990s. The Phelps collection was housed at Emory & Henry for a time.

The photographs on display showcase a number of notions that were regular practice up until the early 20th century. The vast majority of young children seen in portrait photos, whether girls or boys, are in dresses. To facilitate toilet training before the invention of modern jeans, little boys were kept in unbreeched clothing up until the age of 8 when their hand-eye coordination developed enough to handle dressing and undressing themselves in complicated trousers or what was commonly called breeches back then. This rite of passage from dresses to pants was known as a breeching and was considered an exciting moment for boys that was sometimes accompanied by a party or celebration to mark the occasion.

A handful of photos curated for this exhibition show examples of infant and early childhood mortality in the area. The uncomfortable bluntness that these photographs reveal in the faces of deceased youth is a legacy of cultures that had lived since the beginning of history with the high mortality of children. The technological development of the photograph allowed grieving parents and loved ones the opportunity to retain an image of their deceased child outside their own memories in a way their ancestors never had the chance to do. Today, the sheer proliferation of photos and videos in our lives has made these kinds of displays of grief rarer in the public consciousness. But for the parents of yesteryear, these photos were sometimes the only image they possessed of their babies.

What makes these images so especially noteworthy is that these trends lingered somewhat longer in rural Appalachia compared to other parts of the country and, thus, give us a unique snapshot of life in this region.

The photos range from the late 19th century to the 1940s. The majority at from the turn of the century.

For more information about the museum or this exhibit, visit www.williamkingmuseum.org. The exhibit runs from Dec. 3 through March 8.