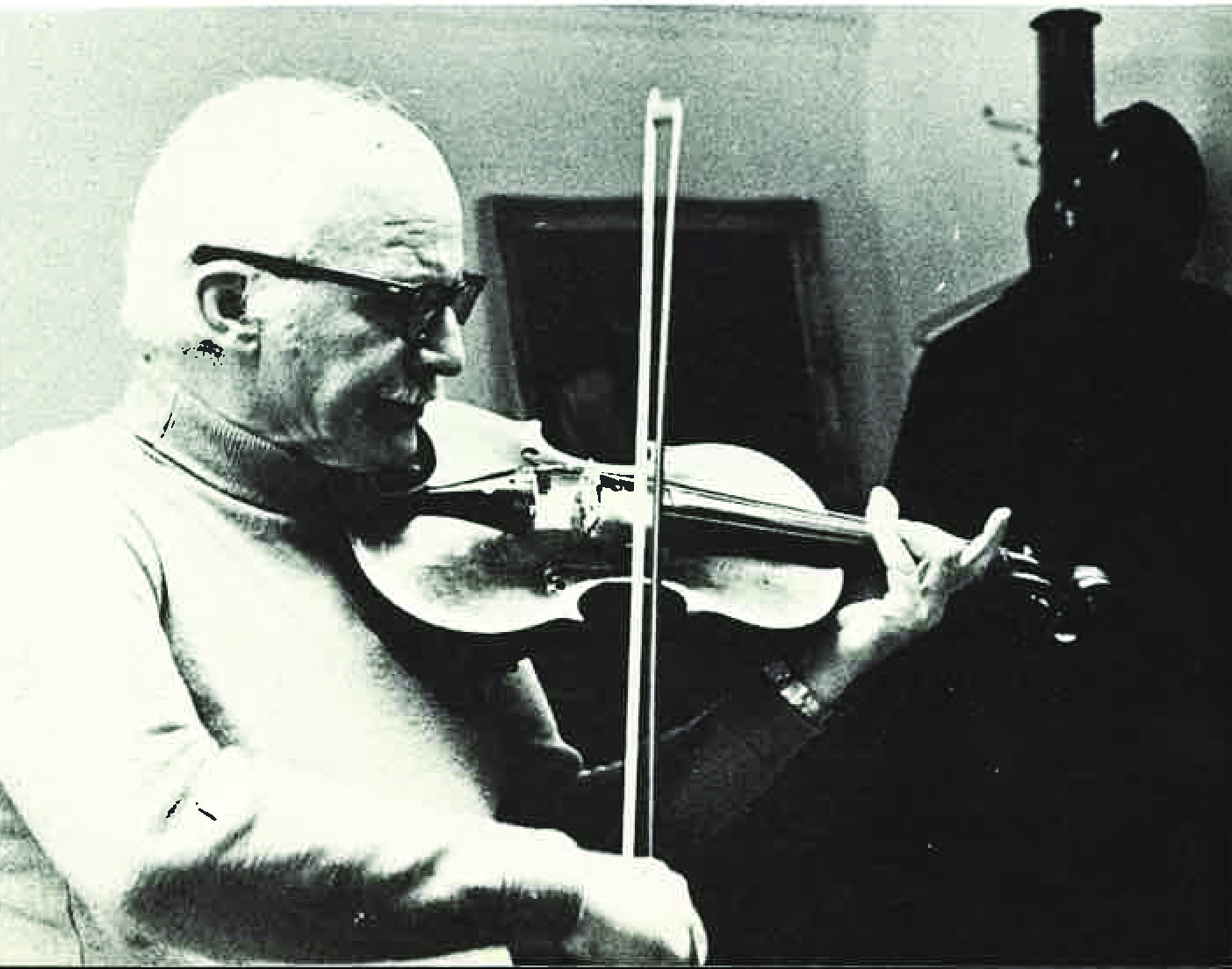

Ludwig Sikorski

Ludwig Sikorski began teaching at Emory & Henry in 1950 and served the college until 1976. He taught the violin, viola and cello, and was praised for his talents in both teaching and performing.

“Alys and Ludwig came for a couple of years in 1950 — or so they thought. Ludwig was exhausted from working so hard and at first he didn’t even think that E&H was a real place. He thought some of his students had put together a fake letterhead. So he didn’t pay attention to the first two or three letters that came. Finally Dr. Gibson called him convinced Ludwig that it was real. So Ludwig took the train down to look the school over. He was met at the train station by five or six students who had formed their own band. He thought well if this is an indication of the student body, this will be an interesting time. There was also a school in Buffalo that was offering him a job. Ludwig asked Alys which she preferred. She thought Buffalo had too much snow, we’ll go to Virginia. The first Thanksgiving we got snowed in. We had a blizzard that’s still on the record books.

“They loved it and loved the students. Every time a few years passed, they’d decided to stay until a particular student graduated, but then there was always another student who was interesting,” Pravda Sikorski Bauer, his daughter, says.

In response to strong student demand, he founded the college’s first marching and concert bands. He also was founder and co-director of a community orchestra, the Highlands Chamber Orchestra, which began small, with rehearsals in member homes, and grew quickly, requiring regular rehearsals on the E&H campus.

“We had a marching band and a concert band. They played at the football games. Ludwig arranged the music for whatever instruments we had. They were always busy practicing for themselves or working with students. Sometimes during the first few years, there was no music for the church service, and they’d do that. We’d find students and get a choir together for an anthem, somebody would do a solo and Ludwig would play. There was always something going on. They’d help students with an act for a talent show. They were always putting together something for some occasion. They sponsored the male singing group, The Collegians, which was student directed. Ludwig would give them advice and arrange music for them,” Pravda says.

The son of Polish immigrants who taught him to play the violin when he was a child, Sikorski was a graduate of Yale University, where he subsequently was awarded a master’s degree.

Before joining the staff at Emory & Henry, he taught at the University of Connecticut and performed for the New Haven Symphony, the Connecticut Symphony and the Yale String Quartet. He received numerous awards for his compositions and arrangement, including the Yale School of Music Alumni Association’s Certificate of Merit for distinguished service in the music field. He also received four Ditson Awards for excellence in theory, history, performance and composition. In 1974, he was selected for the Woods-Chandler Prize for his composition of chamber music.

During music school, he made extra money with his music manuscript writing. “Ludwig had beautiful writing. He’d do a page in about 10 minutes. Many students in music school had terrible penmanship. So, they would hire Ludwig to copy their work for them, so the professor could read it. When there were page turns, he’d fit it so you had time to turn the page. He was very much a trained musician. He could do everything and do it so well. There aren’t many people who have all that in one package.” Pravda says.

In 1985, Emory & Henry honored him and Alys with the William and Martha DeFriece Award for service to humanity.

A Tribute to Ludwig

Emory & Henry has a history of offering brilliant instructors rarely found in rural settings. Not just artists in residence, or visiting professors teaching for a year or two, destined to move on to the next institution. These were giants who stayed for years, even decades.

How many rural colleges in Virginia featured a Yale-educated chairman of the music department? And, how many colleges or universities featured a Yale-educated chairman of the music department, married to his beloved wife, who was an honors graduate in music from Yale University? That is a small Venn diagram, and Emory & Henry College is right in the middle of it.

I was 6 years old when I first met Dr. Sikorski. I walked out of Byars Hall with a cello suitable for a 6 year old. I loved it. The strings, the bow, the rosin ... but it was far more than that. It was smells, sounds, people and experiences that not many kids in Southwest Virginia would expect to have.

Byars Hall was one of the most important places during my childhood. There was the fancy front entrance with the huge columns and the double staircase leading up to the heavy double doors. The back entrance was a different story.

The back addition to Byars Hall was maybe just a little less horrid than Hillman Hall. It had a dumbwaiter system, for some reason. You could stick whatever in the small elevator thing and send it up to the upper floors. I never understood why they needed that, other than to give kids waiting on lesson times something to do with whatever was handy to send up or down to the various floors. And, no, I never transported a human being in one, nor did I ever ride in one myself. In hindsight, the entire thing seemed incredibly dangerous, and I presume it was removed during the renovations to the building.

Anyway, the back entrance opened to a room with a linoleum floor (I think it was brown, maybe) and then, all the magic happened. That was where you walked in if you were there to do business. Reverse mullet. Party was in the front, business was in the back. Bob Denham’s Iron Mountain Press. Chick Davis singing and helping a student/Emory choir member through the intricacies of a part. Students practicing on the many pianos on the top floor. It has been many years ago, but I seem to recall that Alfredo Castellanos taught photography and had a darkroom on the first floor.

And, there was always that smell that was, is, and will always be Byars: pipe tobacco and rosin from Dr. Sikorski’s office. It smelled like ...creativity and music. Every now and then, I’ll smell something that reminds me of Byars. Pretty much the touchstone of Emory & Henry for so many people.

Remembering Dr. and Mrs. Sikorski is so important today. Dr. Sikorski had an aneurysm at his desk. He survived. He played as brilliantly as ever, but he was locked in the years of the war. The Highlands Symphony Orchestra played in the church, and I remember him talking about the difficulties of playing music while the war was raging. I realized that he would ALWAYS keep playing. That was what he did. That was what his beloved wife did.

Keep playing. That’s the best way to honor them both.

David Saliba

Another Tribute

It is appropriate that I am writing this on Super Bowl Sunday. The game will be forever linked with my memories of Highlands Chamber Orchestra concerts which always took place on that day, presumably on purpose. I started my violin studies with Ludwig (Mr. Sikorski to me) when I was in 6th grade, the age when we had the opportunity to start band at Meadowview Elementary. I wanted to play the saxophone or the drums but as I recall, instead of saying “no” my mom said “How about violin lessons?” Clever Mom—she had me hooked and ended an argument before it ever started. I gave up the camaraderie that came with being a band kid, but I loved every minute of my violin lessons.

My memory of Mr. Sikorski’s somewhat cluttered office in Byars, smelling wonderfully of sheet music and pipe tobacco and rosin, is as clear as if it were yesterday. He often shared stories of his time playing under the baton of the great Arturo Toscanini in his days as a violinist in the NBC Radio Symphony. I was delighted to learn that the very dignified Professor Sikorski had also been a wrestler in his youth as well as a trombonist. I cannot recall ever not wanting to play, and whatever innate motivation and ability I came with was perfectly matched with Mr. Sikorski’s kind, patient and supportive teaching. He definitely had high standards but never to the point of causing frustration. Even learning etudes was fun because he never gave me the idea that they might not be.

Mr. Sikorski had his young students sitting in the back of the section in the orchestra as soon as they were able to manage it and I was no exception. I can still remember so many of the pieces we played (Schubert’s Fifth Symphony was the first for me)—most of it real orchestral standards with his wife,Alys, and one of her college piano majors filling in any missing parts on the two Steinways in the rehearsal room. Looking back, what Ludwik and Alys were able to accomplish with that little multi-generational orchestra is remarkable—a tremendous benefit to the young elementary and high school students without a school strings program or a local youth orchestra and to the college students whom they trained and nurtured as well, and of course the community members who never stopped loving to play.

Though I didn’t choose to major in music in college or make a living as a musician, I have continued all of my adult life as an active and devoted amateur violinist, playing in community orchestras and chamber groups and continuing with years of lessons, reaching the advanced level of repertoire that I was approaching by the time I left high school and that I’m sure Mr. Sikorski had envisioned for me. I have my mom’s clever offer and Ludwig’s wise and joyful teaching and his unparalleled musicianship to thank for giving me this amazing gift of being able to play the violin.

Samira Saliba Phillips