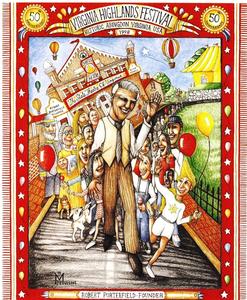

Robert Porterfield was depicted as "The Pied Piper of Abingdon" in the signature art for the Virginia Highlands Festival's 50th anniversary. Art by D.R. Mullins of Shady Valley, Tenn.

Barter Theatre -- whether you know it as your hometown theatre or by its worldwide reputation -- originated with the vision of Robert Porterfield. What began as one man's dream has evolved into a spirit, pride and sense of ownership felt by an entire region -- and one of the Commonwealth's greatest cultural assets.

A native Southwest Virginian, Porterfield grew up with the calling of theatre in his blood -- a dream that took him as a young man to Broadway, just in time for the Great Depression.

Seeing talented actors struggling for food and remembering folks back home with food they were struggling to sell, Porterfield brought these two unlikely groups together. Trading ham for Hamlet, the citizens of central Appalachia in the 1930s could experience top-notch theatre in their own hometowns, while actors who couldn't find work elsewhere could ply their trade and eat well, too.

Battling skeptics every step of the way, Porterfield nurtured Barter Theatre from its humble beginnings into the institution that theatre-goers worldwide know and respect today.

Porterfield died in 1971. His widow, Mary Dudley Porterfield, reminisced about her late husband and "the old days," first with biographer Robert McKinney, then with A! Magazine for the Arts. We visited with Mrs. Porterfield and McKinney at "Twin Oaks," Porterfield's homeplace near Glade Spring, Virginia.

This story is based on her recollections; Robert McKinney's biography of Porterfield, If You Like Us, Talk About Us; and an article entitled "The Barter Theatre Legend" by Barbara Carlisle in Now & Then magazine, which may be found at locations such as Fandango's in downtown Bristol and the William King Regional Arts Center in Abingdon.

Trading Ham for Hamlet

(In addition to the photos at the end of this article, you may view more vintage Barter photos by clicking here.)

"No son of mine is going into that wicked show business!" thundered William B. Porterfield. He wanted his 10-year-old son Robert to become a minister when he grew up, but the siren call of theatre was too strong for the boy to ignore.

Abandoning college after two years, Robert Porterfield opted for New York City's American Academy of Dramatic Arts. His acting career was just beginning to take off when the Great Depression struck, and he found himself out of work, broke and hungry.

Back home in Virginia, mountain folks had no money either, but their cellars and smokehouses were bulging with homegrown food; in fact, they had surplus they couldn't sell. Porterfield wondered, "Why not get a troupe of professional actors, go down to Virginia, and see if live professional theatre can't be traded for cabbages, fresh watercress, and bacon?"

Porterfield started Barter Theatre in 1932. The young theatre went through many tough periods, but Porterfield persevered and succeeded. At the end of the 1933 season, the first company of about 20 actors had accumulated only $4.35 in cash, but boasted a collective weight gain of more than 300 pounds.

When Porterfield was drafted during World War II, Barter Theatre was closed. Private Porterfield joined actors William Holden, Ronald Reagan, Arthur Kennedy, and a score of others in making training and indoctrination films at the First Motion Picture Unit in Culver City, California. Later he had roles in Hollywood films -- including Sergeant York and The Yearling -- but the hills of Virginia kept calling his name. He gave up Hollywood glitter and convertibles to reopen Barter -- and the rest is history: Barter Theatre is now the State Theatre of Virginia, renowned worldwide, and Robert Porterfield is a legend.

Master Strategist, Political Figure

McKinney described Porterfield as "far, far larger than life, and yet a more down-to-earth and humble human being has perhaps never trod the cracked asphalt of Broadway or the stingy soil of a Virginia hillside."

Porterfield never hesitated to surround himself with luminaries. For example, he enlisted First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as a patron and sponsor. Her father had lived in Abingdon, and she lent her support to the state theatre idea on several critical occasions.

In "The Barter Theatre Legend," retired Virginia Tech theatre professor Barbara Carlisle wrote, "it wasn't so simple and unorganized. Porterfield was a master strategist. [For example,] in the summer of 1931 he had lectured at Emory & Henry College and subsequently produced a play with E&H students, touring it to six other towns in the area. During that summer and the next, he laid the groundwork with [Abingdon] for the free use of the Opera House, originally a church but more recently the city hall, and he arranged with the abandoned Martha Washington College to house actors for free."

On a trip to Abingdon in 1932, Porterfield met and enlisted the help of Helen Fritz, a physical education instructor at the college, who became his first wife. McKinney wrote, "Few who have given Barter's history serious thought doubt that without Fritz's keen organizational abilities and tightfisted financial management, Barter likely would not have survived its first season. [Porterfield] was the creative driving force, the ambassador of culture, and the Gibraltar-like symbol of Barter Theatre, but it was Fritz who, quite literally, counted the beans."

In New York, Porterfield persuaded Actors' Equity to let actors work for food, and The Dramatists Guild to accept barter for royalties. In time, hams graced the tables of Noel Coward, George Kaufman, Phillip Barry, Robert Sherwood, Sidney Howard, Rachel Crothers, Howard Lindsay, Fred Allen, and even Clare Boothe Luce.

The late actor Hume Cronyn, who worked in Abingdon the second summer and the fourth, once said of Porterfield, "He was a natural political figure who knew how to persuade."

In 1937, the Barter Theatre troupe made the first of a three-year sequence of New York appearances. Carlisle wrote, "New Yorkers could barter their tickets, and it was a promotional triumph, with coverage in The New York Times, Time magazine, and even The London Times. By 1939 Porterfield had appeared on radio shows hosted by Fred Allen and Rudy Vallee, and he had achieved the height of theatrical tribute, a Hirschfeld cartoon depicting him in the lobby of [Barter Theatre] with audience members trading farm products for tickets."

Porterfield started an annual Barter Theatre Award Luncheon in New York City in 1939, in which he presented a Virginia ham to the actor/actress voted to have made the most memorable contribution to theatre during the previous year. "Thanks to [Porterfield's] personality and contacts, the luncheon always included some of Broadway's most famous people and such well-known non-actors as Eleanor Roosevelt, who presented the first award. The award also included a handmade platter 'to eat the ham off of' and the deed to an acre of near-vertical Virginia mountain land not far from [Porterfield's homeplace] Twin Oaks." In addition, the honoree picked two unknown actors to go to Barter for the summer. Several of those selected went on to become famous: Gregory Peck, Mitchell Ryan, and others.

Publicity made Porterfield a character and a legend in his own time and he began to be besieged with applicants -- eight or nine hundred of them a year. McKinney quoted Porterfield: "The theatrical world heard that I was an offbeat producer who would take a chance on untried young actors. I only paid in produce, to be sure, and I worked the devil out of you, but the climate of Abingdon was reported to be wonderful."

According to Carlisle, Gregory Peck was fond of telling how he arrived in Abingdon and had to learn more than a hundred lines of dialogue overnight. Like many alumni, he regarded that summer of hard work as an important foundation for his career.

Barter continued to attract aspiring performers, helping to launch the careers of many well-known stars of stage, screen and television, including Ethel Merman, Patricia Neal, Ned Beatty, Gary Collins, Jim Varney, Kevin Spacey, Larry Linville and Wayne Knight, among others.

McKinney wrote, "One young man who braved the grueling schedule hitchhiked into Abingdon and told [Porterfield] that he was originally from Connecticut, had been in the regular navy for the past 10 years, and needed work. He wasn't asking for an acting job, he insisted, although he did admit that he had caught the acting bug and had spent a couple of months at an acting school...He ended up staying around for five years." The ex-sailor with the gap-toothed grin was hired to drive trucks, move heavy sets, and act a little. Nine years later, he won an Oscar and became famous as Ernest Borgnine. Later, Borgnine said of Porterfield, "He gave me my start in the business, and every time I see my Oscar, I remember him fondly."

In 1995, John Glover won the Tony Award for Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Play (Love! Valour! Compassion!). In the playbill biography, Glover mentioned that he "began his career at Robert Porterfield's Barter Theatre in Abingdon, Va., in 1963." Intrigued, a Washington Post reporter asked Glover to elaborate. He replied, "It's where my roots start in the theater. I worked down there three summers, 1963 to '65. You had to pay $100 a month and you worked backstage for the summer -- it was like slave labor: painting scenery, moving things. But Mr. Porterfield had a rule -- the person that's right for the part gets the part. That first summer they were doing Look Homeward, Angel and I got the lead! Ned Beatty was in it and Jerry Harden, too. There were artistic ideals that Bob Porterfield set up in my system that I still have today."

A Model for Regional Theatre

Porterfield produced new plays by frequently unknown playwrights. According to the biography, "Barter, from its very first year, always tried to stage two or three new plays a summer, most of them world premieres. One of the reasons for this, [Porterfield] admitted, was that he could produce the plays of new or unknown playwrights without royalty other than a Virginia ham, but the real reason was that he always believed that a repertory theatre has just as much responsibility for discovering and encouraging new playwrights as it has for discovering and encouraging new actors."

He "found the courage to put on other plays that he liked and thought important, no matter what the subject might be. In the process, he said, he thought he educated Barter patrons to become one of the best audiences in the U.S....[He] lost a few customers, of course, but he felt that he gained more than he lost, and that the ones he gained were better-educated and more open to innovation than the ones who left."

McKinney wrote, "[Porterfield] continued to believe that his Barter Theatre could and should make a difference not just in Southwest Virginia, but throughout the country. He believed it could sow the seeds of professional regional theatre wherever it went, and he put his beliefs into action by assembling two touring companies [in 1946 and 1947]."

Porterfield's idea of a regional theatre, beyond Broadway, won him a Tony in 1948. He was a founding member of the League of Regional Theatres and of Theatre Communications Group, both organized in the 1960s to assist the emerging professional regional theatre movement.

Carlisle continued, "Barter is often cited as one of America's first regional theatres, and with his triumphal achievement of getting Barter Theatre named, in 1946, The State Theatre of Virginia, Porterfield genuinely hoped to be creating a national model."

McKinney wrote, "As America's first state theatre, everyone involved with Barter felt upon them the eyes of the entire theatre world and of state legislatures throughout the country, intently watching to see if Porterfield and his people proved that regional professional repertory theatres could survive far from major cities."

Barter continued to grow, extending its tours, adding children's plays, building a second stage -- and its own legend. During the spring of 1962, the Old Dominion Foundation offered Barter a $100,000 grant to consolidate its resources and establish a perpetuating foundation to help ensure the theatre's survival -- on the condition that Porterfield raise another $25,000 in matching funds from local individuals and that the board of directors be reorganized so that it would have more direct contact with the theatre's operations.

McKinney wrote, "[Porterfield] had always liked to have a board of directors that pretty much kept its hands off day-to-day operations, but he was also practical." The Barter Foundation was incorporated, and by October, Porterfield had raised more than $30,000 to match the grant funds. Porterfield, his new board, and the Commonwealth "all seemed determined to give Barter a life of its own that would continue beyond the 'four score and seven' allotted to mortals."

Civic-Minded, Community-Oriented

Porterfield was also a charter member or former director of several organizations promoting tourism in Virginia, and he was extensively involved in civic projects throughout the region.

He received numerous honors during his lifetime. Although many of these awards reflected his contribution to American theatre, others pointed to his overall civic contributions.

Porterfield's foresight enabled Abingdon to distinguish itself, creating the myriad of opportunities that led to individual opportunity. Barter Theatre has helped to make Abingdon a tourist attraction.

Of Barter's current artistic director, Carlisle wrote, "Richard Rose is keenly aware of and in tune with the need for development of material from and about Appalachia as part of his mission. Barter's Appalachian [Festival of Plays and Playwrights] is now in its ninth year. Barter still auditions actors in New York but holds regional auditions as well."

She concludes, "It is a big step for a regional theatre to grow up and stop looking over its shoulder to New York, to recognize that its own narratives have a place beside Neil Simon's Manhattan or Tennessee Williams' dying Deep South....It was not Porterfield who imagined a place for Appalachia in theatre, but it was his imagination that continuously kept alive an institution in Appalachia where theatre would flourish. And in doing so, in maintaining that legend, he provided a place where eventually the region would have a voice alongside all those others."

Virginia Highlands Festival

Although he is best remembered for founding Barter Theatre, Porterfield did much more to improve the quality of life in Southwest Virginia. Always interested in the economic development of the region, Porterfield was a founder of the Virginia Highlands Festival, now in its 59th year.

The purpose was to preserve and celebrate the cultural heritage of this area. The Festival has grown into a regional festival representing all of Southwest Virginia. Now it not only preserves the arts, crafts and skills that developed in this region, but also imports talented artists and performers from all over the U.S. and the world for the enjoyment of area residents and visitors.

The first Virginia Highlands Festival was held in 1948 on the front porch of The Martha Washington Inn, in conjunction with the Barter Theatre Drama Festival. The first printed program for the Festival proclaimed that it grew out of Porterfield's desire to establish in the Virginia Highlands a center for all the arts. The first Festival was basically an institute, with lecture/panel presentations on topics including Education in the Arts, Drama and Its Ramifications, Modernism in Music and Related Arts, and Virginia Poets. Activities included a piano recital, a ballet by Constance Hardinge's company in Bristol, and a demonstration of crafts, exhibits of art and photograhy, and folk dances and ballads of the region.

When the Festival celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1998, the event was dedicated to Porterfield, whose energy, enthusiasm and vision guided the Festival through the years. According to the 50th anniversary booklet, "There are some who feel that Porterfield, whose Barter Theatre actors had performed at White Top, wanted to expand the concept and develop in Abingdon a festival that would bring together not only various aspects of the region's cultural heritage but also cultural expressions from other regions, for both entertainment and study. [This reflects] a basic purpose of the Festival that has remained constant...Granted, the Festival has become more complex and provides, it seems, 'something for everyone,' yet it is still focused upon the arts and crafts. It succeeds in demonstrating the truth of the words of Porterfield, spoken at the first Festival: 'The immense work of the arts cannot be measured in dollars and cents, but in the amount that it enriches the individual and the community's cultural and civic life.'"

For the first few years, the Festival only lasted three to five days, but in 1952 it was extended to two weeks, which is the length of today's Festival.

Mrs. Porterfield, formerly Mrs. Vance of Vance's Tavern Antique Shop, was once in charge of the first Antiques show. At that time, there were 10 exhibitors (with an emphasis on the word "exhibitors") in the ballroom of the Martha Washington Inn. No items were offered for sale; dealers answered questions and specialists lectured. Today 75-100 antiques dealers from throughout the southeastern United States sell their wares in huge tents on the campus of Virginia Highlands Community College.

At first, crafts were not officially sold, either. Artisans demonstrated Appalachian traditional crafts and taught classes. Other workshops were offered in creative writing, fine arts, music, and photography.

When the first Festival was held, musical performances fell into two broad categories: traditional Southern Appalachian and classical music. The presentation of traditional music was consistent with one of Porterfield's purposes in helping to establish the Festival -- to make it a continuation of some aspects of the famed White Top Folk Festivals of the 1930s. Through the years, the variety of music has expanded. Today, musical performances include bluegrass, country, folk, classical, jazz, gospel, rock-n-roll, blues, and more.

In the Festival's 50th anniversary publication, the late Mary Agnes Miller recognized the event's cultural impact: "Don't you think the interest in art in the community has been in part due to the Festival? We have the William King Regional Arts Center and the Arts Depot. These things didn't exist before...I think people are hungry for things they can participate in."

Over the years the Festival has expanded at an incredible rate, as Festival board member Lovis Countiss explains, "We have lots of new people coming to Abingdon, and these people have certainly been an asset to our town. With this, they have new ideas that they have brought with them. We have found that if the [antique] dealers come to the Festival and have a good year, they are going to talk to other people about it, and other people are going to want to come."

Another Festival volunteer, the late Frances Moore, recalled, "There have been a lot of celebrities here...Gregory Peck, Ladybird [Johnson] and her cabinet...She had two chapters [in her diary] on Abingdon."

Besides educational events, the first Festival also included a Historical Society tea and private cocktail parties, things that Mrs. Porterfield sorely misses. The second year, a costume ball was added. The next year, five historic homes were opened to visitors, creative writing workshops began, and three teas were held. The Festival's 50th anniversary booklet describes tea time as "a social time when hospitality is Southern and gracious and one's senses can be soothed by a carefully prepared tea environment."

Opening historic homes to visitors appealed to tourists as well as area residents. Most people agree that a key element of the Festival's success is the setting of Abingdon's historic district. Few other towns provide such a rich and varied collection of buildings spanning a three-century period with such close proximity to each other. By 1953, a two-day tour offered 24 home sites and buildings open to the public. Today, visits are limited to kitchen tours in a handful of homes, not all of them historic.

And today, the Festival is recognized as one of the Top 100 tourist events in North America, the Top 20 in the Southeast, and the Top 10 of Virginia.

Memories

(In addition to the photos below, click here to view more photos of Porterfield, his family and friends.)

Mary Dudley Porterfield warmly welcomed us into her home. Throughout the afternoon she shared memories of her late husband, describing him as the most charming man she'd ever met. "He was a marvelous dancer," she recalled with a twinkle in her eye. "Bob loved life and he genuinely loved the people here, too."

The first time she saw Porterfield's face on the cover of his biography, she smiled and said, "Hello, darling!" Since the book came out, Mrs. Porterfield says she has been overwhelmed at the response: "I've had so many phone calls and letters from people who knew Bob and from people I didn't know knew him. Many of them tell me the book has brought back so many memories."

She continues, "Bob never got discouraged to the point that he felt like giving up. His mind was always so busy with new ideas. I hope the book inspires young people, to feel like they can do anything they put their minds to and pursue their dreams. I'm just sorry that young people today didn't get to know Bob themselves."

McKinney noted, "He could have taken an exit at any time from his dream. When he was out of work as an actor, he could have stayed home and run the farm, or he could have become a minister, a politician or a Hollywood star, but he didn't."

Mrs. Porterfield replied, "If he had taken an exit along the way, our paths might not have crossed, and I might not have known him, either."

She met her first husband, Charlie Vance, over brunch during a sorority house party in Mississippi. When she visited Vance in Abingdon, she met Porterfield and their friendship began. She married Vance in 1948 and took up residence over The Tavern, which housed Vance's antique shop on the first floor.

Asked to compare Abingdon then to Abingdon today, Mrs. Porterfield laughed and said, "Back then there was no Arts Depot, no Cave House Craft Shop, no William King Arts Center. Of course, Bob always said if it weren't for Abingdon, Marion and the Tri-Cities, there would be no Barter Theatre. I made the remark one time, during the Highlands Festival, that if Bob came back, I'd say, 'Look at this monster you created!' It's huge!"

When her first husband died in 1963, she retreated, grief-stricken, to her girlhood home in Bolton, Mississippi. Porterfield lured her back to Abingdon by asking her to head up his Friends of Barter program, which promoted ticket sales.

"I had never stayed by myself in my life," she said, "so I stayed in a room at The Martha Washington Inn for a month before deciding, 'I'm a big girl.' Then I alternated, staying one night at The Tavern and one night at The Martha."

When the Friends of Barter program successfully concluded after six months, she accepted a position with the Washington County Chamber of Commerce, which had offices in the front of Barter Theatre, across the entrance from the box office. She remembered, "When Bob was in the ticket office, I could see him, so he made faces at me and waved." The friendship grew friendlier, one thing led to another, they "eloped" to Mississippi in 1964 and spent their honeymoon in New Orleans. In 1968 they adopted a five-year-old boy they named Jay Payne Porterfield, (nicknamed "Jay Bird"), who grew up to have a son of his own.

In 1971, despite suffering from a bad cold, Porterfield insisted on attending a play in Washington, D.C. and then visiting New York. He became more ill and ended up in Johnston Memorial Hospital's intensive care unit, where he spent the last days of his life. He was 65.

McKinney wrote, "Praise for [Porterfield] and his work came in from all over the world: from congressmen, famous actors and actresses, the governor of Virginia, and President Richard Nixon, who personally telephoned Mary Dudley. But it would have been the outpouring of condolences from the local mountain people, the farmers and laborers and the planters-of-rows-of-extra-beans [to barter for tickets], that Porterfield would surely have cherished most."

Where to Find More Information

Copies of Robert Porterfield's biography If You Like Us, Talk About Us (hardcover $27.95, paperback $18.95) are available at Barter Theatre's gift shop. Call 276-628-3991 or email giftshop@bartertheatre.com.

For more information about Now & Then magazine call the East Tennessee State University's Center for Appalachian Studies and Services at 423-439-7994 or email nowandthen@etsu.edu.