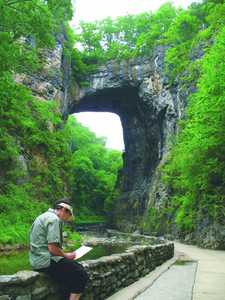

Suzanne Stryk sketches at Natural Bridge.

Suzanne Stryk’s “Notes on the State of Virginia†begins March 1 at the William King Museum of Art, Abingdon, Virginia.

The show closes July 15. The show contains 26 “assemblages,†which is how they refer to Stryk’s layered artwork. It has been on tour across the Commonwealth of Virginia since 2013. It concludes its tour at the University of Virginia later this year.

Callie Hietala, a curator at the William King Musem of Art, conducted this interview with Stryk. We use it here with permission.

Callie Hietala: What brought you to this particular project?

Suzanne Stryk: Shortly after moving to Bristol from the Midwest in the late ‘80s, I jotted down the title of Thomas Jefferson’s book, “Notes on the State of Virginia,†for a future project of my own. I thought it would be fascinating to one day explore the state on a personal mission with sketchbook and collecting bag in hand. But such an intimate activity on such a large scale? "well, it took me decades to get a handle on how to do it. In 2011, with a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts, I finally began the project."

CH: How did you go about choosing which locations you wanted to represent in this body of work?

SS: As you might expect, I included some well-know sites associated with Jefferson, such as Monticello. And then I let my own curiosity guide me in selecting natural areas unique to Virginia "a sanctuary for an endangered species, a pristine wetland, a salamander-rich mountain habitat and so on.

I chose a few urban or historical sites, looking at them from a naturalist’s perspective. At Appomattox, the human drama eclipsed the wild one, so I layered images of Civil War artifacts over tree leaves. In Richmond, I wound up spending days at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts with campstool and sketchbook as if I were doing fieldwork. I drew animals in art from all over the world, stumbling on a way to reflect the diversity of that city’s people.

CH: How have you been influenced by Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia?â€

SS: Well frankly, my intention was to use his text as the launching pad to my own project. Best way I can explain it is to give you a couple examples of how the link to Jefferson gave a deeper historical background to my own ramblings.

In 2011 as I zoomed down Route 64 from Staunton to Charlottesville, it dawned on me: in the late 1700s, Jefferson traveled along this very byway on horseback. Imagine what he’d have seen on such a slow trek. Or another way of looking at it, imagine what I missed at 65 miles-per-hour. With that thought, I pulled over at Rockfish Gap Overlook to sketch and as it turned out, pluck a buckeye butterfly from my Subaru’s grill. It wasn’t lost on me how strange that that small act would be to someone 200 years ago.

Later that summer, I made a pilgrimage to Jefferson’s retreat, Poplar Forest, where he wrote the bulk of his book. And where they’re now unearthing artifacts from his day. When I crouched close to an excavation pit there, breathing the sweet earth-scent, I caught the glint of a blue-and-white shard of pottery stuck in clay. Well, that totally blew me away to think of how the mystery of the past mingled with my visceral present.

So, you might say my project’s link with Jefferson’s Notes creates a historical arc to my Virginia here and now.

CH: Has the project changed at all from how you originally conceived it, or has everything gone pretty much according to plan? Any surprises along the way?

SS: No matter how much I’d prepare beforehand, read up on the locale, sometimes even arrange to meet with a local guide, there were surprises.

Because when my boots actually scraped the earth or as I paddled down a river, well, that’s when the unexpected kicked in. After all my planning, I’d let myself be caught up with whatever grabbed my attention: ravens muttering to each another? A crayfish hiding among the mussel shells? A fisherman grousing about his catch? I was sidetracked by design, you might say . . .

Case in point: My plan at Douthet State Park in the Alleghenies was to survey plants and animals, but I ended up chasing after an orange-headed skink for hours.

CH: Why did you choose mixed media?

SS: I never intended to make “pictures†of places, but rather documents of experience. I felt that found objects, maps, surfaces rubbed with coal or earth, specimen boxes, along with drawn and painted images, would convey that best.

CH: Yes, I see in these pieces plants, tree bark, nails, rock dust, grass, even blood, do the materials used to create each piece relate specifically to the location you’re exploring, or do you use whatever best suits your aesthetic needs, regardless of where you collected it?

SS: Materials derive from the specific site. You mention nails. Well, those in “The Green Fuse†I gathered in an old Shenandoah Valley barn, along with rusty remains of farm machinery and a scrap of leather shoe. Hovering over those artifacts in the assemblage, I placed my painting of kestrel wings. So why did I paint them green when the hawk’s true feathers are gray to black? Because the piece is about grass as the source of all life on the farm, human, insect, rodent, hawk, whatever. My neurons start firing when nature and culture collide like that.

CH: As you’re collecting objects, are you looking for specific things? For example, are you already thinking, “Oh, I want to incorporate this into a piece so I’m going to seek it out,†or “This looks interesting, I might want to include it in the work?â€

SS: Definitely the latter, I collected first, then decided what to use. You should have seen my studio tables as I worked. Ziplocs full of clay, bottles of swamp water, fishy sea wrack, crumbling dragonflies, cane from the banks of the Clinch River, moth cocoons . . . you name it. Add to that heaps of sketches, maps, even tourist pamphlets. What a jumble.

And what a challenge settling on one approach to an assemblage, so many choices. I’d asked myself: “What resonates with me about this place†and go from there.

Assemblages such as “The Dragon†brim with local finds, while others, such as “Flyway,†are simplified. Not that I didn’t make copious observations on the Eastern Shore that September I did. But on my last morning, as I hiked around Cummings Birding and Wildlife trail, suddenly. Whoosh! hundreds of ducks rose from the salt marsh at once. I’d frightened them into a whirring frenzy as they refueled for the next leg of their journey south.

And so a vortex of feathers over a globe-like egg suggests all the migratory birds witnessed there.

CH: Did you see things you did not expect to discover on your travels for the project?

SS: Yes, but often I didn’t see things I did expect. For instance, at Dismal Swamp I imagined I’d spot egrets in the cypresses surrounding Lake Drummond. But I never made it to the lake the rain just got too hard and pesky mosquitoes came out in droves. So on the slow walk back I discovered things like a green snake winding around a tupelo branch that I might have missed on a fast trek down Washington Ditch Trail. In fact, that’s when it hit me: that “ditch†would have been dug by enslaved people. I stood there in the rain imagining men’s exhausting work knee-deep in mire fending off insect bites. Unforgettable.

CH: How have you noticed changes in the environment since you started making “Notes�

SS: I’m glad to learn that since creating my series there’s an effort to cleanup the mercury in the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. But it seemed when I assembled “Coal Tattoo†that Mountain Top Removal’s days were numbered now I’m not so sure.

In my own life, I’ve noticed some species becoming more tolerant to human habitation, for instance, Cooper’s hawks nested in an old oak behind our house in Bristol last summer. And in a wider sphere, I’m super happy to see the Blue Ridge Discovery Center emerge to teach children and adults about nature. I believe, by the way, that art and science should be partners in connecting people to the living world.

CH: How does your background as a scientific illustrator influence the way you make your art?

SS: If you could see me in the studio, hunched over my magnifier lamp, painting the delicate hairs on a beetle’s leg, well, you’d have no doubt it still influences me.

Take the insects in “Waterway,†set at Big Laurel Creek. I’m in bliss meticulously studying those bio-wonders. Yet I also have an equal urge to create a layered pattern with their horizontal and vertical placement. You might say I blur the boundaries between the art and natural worlds. Always have. Recently when at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, I was looking at minute threads of silk embroidery, and it reminded me of something . . . then I figured what: those delicate insects scuttling at the bottom of an Appalachian creek!

So you see, I just don’t think either/or when it comes to nature and art. Or history. It all intertwines.

THERE'S MORE:

Stryk: From scientific illustrator to artist