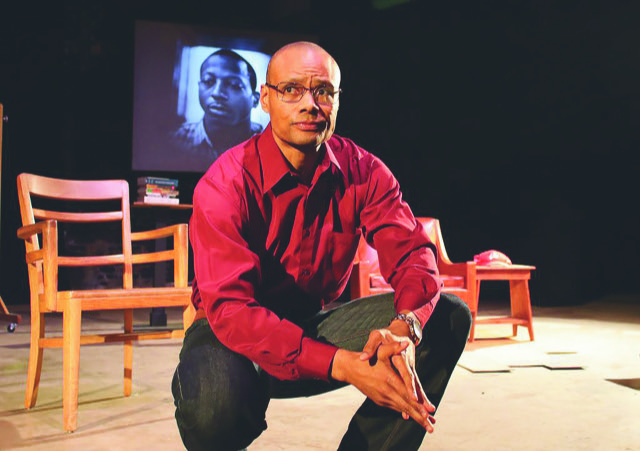

Sonny Kelly

Racism is a difficult topic for conversation for many – but not for Sonny Kelly whose “The Talk” approaches the topic with love. Arts Alliance Mountain Empire and the Virginia Commission for the Arts are bringing his theatrical experience to Bristol Virginia Middle School, Feb. 18 at 7 p.m. The performance is free and open to the public.

“Rather than a play, I prefer to call‘The Talk’a theatrical experience. It’s something you will never forget, and it somehow challenges and inspires us all to do better by each other in the end. I ask people who are uncomfortable about racial dialogue, or who are averse to discussions around diversity, inclusion, privilege or racism to open their hearts and minds to this particular experience.

“There’s nothing like live performance.It forces the audience and me to deal with each other as authentically as we can in that moment. It challenges us both to put skin in the game. If we look away, or choose not to engage, that is a choice that we both see and feel. This medium allows me to call people in (as opposed to calling them out) in a dynamic and connective way that other media just can’t quite achieve.

“This will not be about guilt, shame or kicking dead horses. It’s about naming my own experiences, trying to fit them into the American experience, and challenging myself and others to commit to making new experiences that can exceed our lowered expectations of each other. ‘The Talk,’for me, has become a ministry of reconciliation. Because love never fails, I expect to have plenty of energy and purpose to drive me forward as I continue to share my experience, till it becomesourexperience, around the world,” he says.

“The Talk” with its positive message came from pain. Its origin was the talk that Kelly had with his son.

“The death of Freddie Gray and the start of the 2016 riots in West Baltimore was the impetus for me even having ‘The Talk’ with my son. We were listening to the story on the radio, and I had to tell this wide-eyed little boy something to make sense of all of the violence and heartache. Emmett Till’s story rose up as I reflected upon the fact that his situation and ultimate demise were not unlike those of modern-day criminalized and dehumanized black youths like Trayvon Martin and Kalief Browder.

“I wrote ‘The Talk’ because having to explain what racism means to my 7-year-old son was a genuinely traumatic experience for me, and I needed a way to digest it. As an artist and a scholar, I wrote ‘The Talk’ as a means of making sense of the strange and paradoxical race talks that people of color tend to have with their children. As I began to rehearse and perform for audiences, my intention expanded. ‘The Talk’ has now become a launching pad for intercultural and interracial conversations about healing, unity and transformation” Kelly says.

Originally, “The Talk” was an eight-minute experimental piece, but that all changed when Kelly showed it to his mentor, Professor Joseph Megel, at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Sharing it led to an arduous journey for Kelly.

“He urged me to dig deeper and write more. I saw this elderly white man crying over my personal experience. That was the spark that started the all-nighters, frequent workshops and rigorous rehearsal and re-writing schedule that took about two years. Joseph Megel became the director of the piece, and it has flourished along with our understanding of racism and the power of love that can dismantle it.

“For research, I watched films like 13th, Time: The Kalief Browder Story, and Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin story. These stories melded themselves to my own story and enhanced my understanding of what it is to be a black man in America, but, even more importantly, what it is to treasure an amazing black boy in a world that often treats him as fungible,” he says.

Kelly plays more than 20 characters in the show. “The audience favorite is my father, Pop. He’s a no-nonsense veteran in his late 70s who built his life on duty, honor and country. He grew up in the segregated south and learned to roll with racism’s punches, while preserving his own dignity and patriotism.I play my mother, who is an amazing woman who has taught me a tremendous deal about learning to love yourself. She grew up as a very light skinned black woman in a black community that always referred to her as, “That White girl.” All her life she struggled to fit in. When I was born a brown child, I became her “brown baby Messiah,” and her hope for a new understanding and expression of identity. I play my maternal grandmother and my paternal grandmother, as well as my big brother, the police officer who gave me my first ticket, my DMV driving test proctor, several students I encountered growing up in Orange County, California, and a few other memorable characters,” he says.

He also embodies real historical figures, as he performs oratorical interpretations. Audiences will meet General Robert E. Lee, Confederate veteran and KKK supporter, Julian Shakespeare Carr and David Duke. They will also meet Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Mamie Till, Eric Holder and Barack Obama.

“The Talk” is about the conversation between Kelly and his son, but there is another talk in Kelly’s life – the one he received from his father.

“I think that ‘The Talk’ I received from my father was not as painful or laden with emotion. My father survived the ‘50s and ‘60s in a deeply segregated small town in South Texas. He gave me ‘The Talk’ in the late ‘80s in Orange County, California, where the weather was sunny and the racial climate much warmer than what he grew up in. So, he felt more confident and positive about the whole thing. Don’t get me wrong, Pop’s talk was still grave, stern and eerily aware of the stakes. However, it was also more matter-of-fact and hopeful that I wouldn’t have to confront violent racism ever.

“My talk is laced with the lament of a man who knows that he should not have to be giving this talk in the first place. Add to this the bone chilling fear that strikes my heart, and the hearts of so many caregivers of black youth, when we hear about another black person gunned down, falsely arrested, harassed, or otherwise threatened by an authority figure or person of power bearing lethal force. I was also adamant about making sure that I did not steal my son’s innocence or plant anger or fear into his heart and mind. So, my talk was much more anxiety ridden and awkward,” he says.

After performing for 80 minutes, Kelly holds a post-show discussion with the audience. While you might think he’d be exhausted after his intense performance, he says instead he’s exhilarated.

“I feed off of the audience. I feel so affirmed and loved when people listen to my love story about how much I truly love my son (now, my sons). It’s for me a tremendously regenerative time of sharing and connecting. We laugh, we cry some more, we argue our points and we agree to do better by one another,” he says.

“I think the most common question I get is, ‘Do you have this on film?’ So many people want to share this experience with their children, family members, friends and colleagues. It’s a powerfully moving experience for me every time. And, while I agree that producing a film version will be helpful to spread the message of love, inclusion and equity that I teach through the piece, it would have to incorporate some kind of live discussion or interaction somewhere in there. Like I said, putting skin in the game by sitting, talking, breathing and dealing with each other is a huge reason why this experience is so engaging and moving.

“I also get the question about black girls. Do black girls get different talks? They do. While I do not have daughters, I have goddaughters, and I mentor black girls. The challenges that black girls face today are even more insidious than those faced by their male counterparts. In addition to being disproportionately criminalized and disciplined in schools and communities, black girls, like women in general, tend to be sexualized and expected to perform according to certain gender norms. So, if a black girl expresses her discontent, she has to constantly be wary of how she does it, lest she be seen as the “angry black woman,” which transforms her into a threat for some — a threat that they feel the need to neutralize violently, sexually or both.

“People often lament the difficulty they have addressing racism with family members, friends and acquaintances who are either uncomfortable with, or offended by, the conversation. I can only say that my experience has taught me that ‘love covers a multitude of sins.’ I say that if you lead looking for reconciliation, rather than looking for a fight, you may just get somewhere. I don’t have to convince you that my experience is true. I just have to care about you enough to show it by listening and sharing. As we begin to get to know each other and care more about each other, we can share our stories and start to deal with them person to person, rather than party to party or race to race,” he says.

For more information about Kelly, visit www.sonnykelly.com.