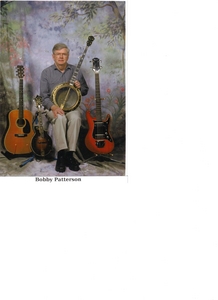

Bobby Patterson is a key link between local musicians and the community.

RICHMOND, VA -- The Virginia Heritage Awards were presented for the first time on Oct. 9, 2009, at the Richmond Folk Festival.

The Virginia Heritage Awards honors Virginia masters of the traditional arts for their contributions to the cultural heritage of Virginia and to recognize preservationists of traditional culture. Masters of traditional art forms exhibit a long-standing dedication to that art form, a high quality of skill within the genre, recognition of "master" status by their communities, and a role in sharing their skills with others in the community.

Winners from Southwest Virginia include the following:

* Bobby Patterson, whose mother played guitar, and his maternal grandfather and three uncles were all musicians. On his father's side, his father and his five brothers were musicians. Patterson started playing the guitar at age 6. By age 18, Patterson was playing the banjo with different bluegrass groups.

In 1972 he built his first recording studio, created a record label, and started recording and producing albums, first as Mountain Records and later as Heritage Records. In 1976 Patterson recorded Wayne Henderson's first album with Ray Cline and Herb Key. In 1987 Patterson helped start the Old Time Herald magazine, a national publication dedicated to old time music.

Today Patterson is still a key link between local musicians and the community. He serves on the Galax Tourism Advisory Board and the Chestnut Creek School of the Arts Advisory Board. As president of the Blue Ridge Music Makers Guild since 1999, Patterson works with emerging youth musicians year-round, helps organize festivals and concerts, and promotes traditional music. As a leader in the Galax Moose Lodge (Governor 2006-07), he organizes the annual Galax Old Fiddler's Convention, considered one of the oldest and largest fiddler's conventions in the world.

* The Rev. Frank Newsome preaches at the Little David Church in Buchanan County, Va., where he has lived for the better part of 45 years. Frank and his congregation are part of a sub-denomination of the Baptist Church known as Old Regular Baptists. While their numbers are comparatively small, their rural locations, predominantly around the shared borders of West Virginia, Virginia and Kentucky, and their strict adherence to church doctrine have helped the Old Regular Baptists to maintain many of their religious folkways.

Because Old Regular Baptist Church doctrine forbids musical accompaniment in their services, the congregation sings a cappella. This tradition consists of a preacher -- often referred to as an elder -- singing a line of hymn, and the congregation repeating the same line in a mournful blend of voices. This style and practice was particularly well-suited to the demands of the early churches, its call and response format allowing participation from those in attendance, many of whom could not read words or musical notation.

One of 22 children, Newsome began attending Old Regular services with his mother as a child. By the time he was 20 years old, Mr. Newsome had moved to Virginia to work in the coal mines. He had his experience of Grace while mining in 1963 and began to preach at the Little David Baptist Church soon after. Frank put over seventeen years "under the mountain" before he contracted the dreaded black lung disease, an all too common affliction for those who toiled underground.

* Roy Odell "Speedy" Tolliver is a native of Virginia's southwestern highlands. Like many musicians of his era, he began playing as a child by secretly picking out tunes on an instrument -- in his case a banjo -- that belonged to a family member. He was nine years old in 1927 when the pivotal Victor Talking Machine Company recording sessions were taking place in Bristol. As a teenager, he was consistently among the prizewinners in the banjo competitions in southwest Virginia.

In 1939, at age 21, Tolliver made a life-defining decision to migrate, along with legions of other southern highlanders, to the Washington, DC area. The country scene in Washington was beginning to blossom with music both by and for the white Southerners who had come to the nation's capitol looking for work and a better life. As a multi-instrumentalist, Tolliver was part of a succession of professional "hillbilly" bands that played regularly around the Washington metro area.

In 1950 Tolliver gave up his life as a professional musician for a regular job and to care for his growing family in Arlington. In the late 1960s he resumed competitive playing and began to collect ribbons from contests at festivals in Galax, Virginia and Clifftop, West Virginia.

Now in his 90s, Tolliver still plays several times a week in jam sessions or as a member of various bands. He continues to teach students in his home, to perform and to compete. Speedy's musical development was influenced by and therefore accompanies the story of the depression era Appalachian migration and how rural culture changed and was changed by the urban environments it touched.

OTHER WINNERS

* Joyce Pale Moon Krigsvold was born on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation in King William County, Va., and learned traditional pottery making from her mother and her aunts. Krigsvold still lives on the Pamunkey Reservation and can be found nearly every day either managing the Pamunkey Museum or creating new pottery at the Pamunkey Indian Pottery School.

Upon their arrival in the spring of 1607, English settlers depended on the generosity of the Pamunkey Indians. The English ate meals with the Pamunkey and became familiar with the earthenware pottery used by tribal members to both store and cook food. Although this type of pottery was new to the English, Virginia Indians had been producing it for thousands of years. Today pottery is no longer used for its original purpose, instead being used almost exclusively as art.

With less than 100 Pamunkey Indians remaining on the Indian Reservation, few potters are left. Krigsvold has taken on a leadership role in the tribe to pass down the techniques and knowledge essential for the tradition to stay alive. She regularly holds classes for younger Pamunkey potters demonstrating the various methods of pottery making. She is also a featured speaker at schools throughout Virginia, sharing her insight of her tribe and pottery making skills to students. Without Krigsvold's steadfast determination and efforts to continue the tradition of pottery making, this art would almost certainly go the way of so many other Indian traditions.

* Grayson Chesser epitomizes the carving traditions of Virginia's Eastern Shore. The son of a game warden and hunter, he spent much of his childhood duck hunting in the marshes around the Chesapeake Bay and collecting hand-carved decoys the way other boys take up model cars. Today he is one of the most respected decoy carvers of his generation, having learned carving at the feet of masters like Cigar Daisy and Miles Hancock. "Kids I went to school with," Grayson often tells, "they all wanted to grow up to be the next quarterback for the Baltimore Colts. Me, I always dreamed of being a decoy carver and goose guide."

Chesser's decoys are highly valued on the collector's market, but his preference is still to carve decoys for hunting purposes. In 1995 Chesser wrote the definitive guide to decoy carving, Making Decoys the Centuries-Old Way. He became a game warden himself and has a lifetime of experience both hunting and regulating the hunting grounds of the region.

Chesser has paid homage to those who taught him in his youth by participating in the Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program. His interest and commitment to teaching the nuances of this tradition are what make him such an invaluable part of the carving community of the region.

* Evangelist Maggie Ingram was born July 4, 1930, on Mulholland's Plantation in Coffee County, Ga. Ingram worked in the cotton and tobacco fields with her parents. It was a hard and humble beginning, but the Lord had a special place for her in life, and she accepted the call at an early age. At 16 she married Thomas Jefferson Ingram whose family also worked as sharecroppers in Georgia. The couple had five children and moved to Miami, Florida, where the father was called to the preaching ministry. Though times were tough, the family was determined to help in the ministry. Ingram took odd jobs as a domestic and taught her children to sing harmony. Sister Maggie Ingram and The Ingramettes were soon a sought-after group to sing at churches, gospel festivals, auditoriums, church conferences, and other places throughout Florida.

In 1961, Ingram moved her family to Richmond, Va., where she began a prison ministry with her children. On the fourth Sunday of each month she and her children would travel to Unit 13 in Chesterfield where they sang and played for the prisoners, along with speaking the word of God. In the early 1980s she received her call to the preaching ministry and was licensed Evangelist Maggie Ingram by the Church of God In Christ.

*************

The Virginia Commission for the Arts supports the arts with funding from the Virginia General Assembly and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Commission distributes grant awards to artists, arts and other not-for-profit organizations, educational institutions, educators and local governments and provides technical assistance in arts management. For more information, visit www.arts.virginia.gov or call 804-225-3132.